Alan Wilkinson

Clare Howard

Alan Wilkinson

Clare Howard

Johan Vandenbroucke

Philip Dean

Rachel Dixon

Richard Hey

Measures to improve the safety of intravenous magnesium sulphate injection seemed simple but required thorough planning and sustained effort for implementation, according to Clare Howard (Clinical Lead – Medicines Optimisation, Wessex Academic Health Science Network (AHSN)) and Anna Lappin (Medicines Governance Pharmacist, Northern Health and Social Care Trust, Northern Ireland).

Between January 2010 and December 2012, five incidents of death or severe harm related to the administration of injectable magnesium were reported in England. The problems arose because the only product available was magnesium sulphate injection 50% w/v, but doses were variously expressed as grams, milligrams, millimoles, or percentages, so that calculations and dilutions on the ward were required. The complexity of the calculations led to frequent errors. Magnesium sulphate is recognised to be a ‘high-risk’ injection.

Wessex Academic Health Science Network (AHSN) undertook a local survey of magnesium use and recommended the use of 20% w/v ready-to-use (RTU) magnesium sulphate injection. However, “the implementation of such a seemingly simple measure can be surprisingly difficult in practice”, according to Ms Howard.

Traditionally, magnesium sulphate injection is used in the management of pre-eclampsia. One hospital in Wessex was already using 20% magnesium sulphate injection and midwives were keen to have the product. One commented that a dose could be given more quickly and this was important if the woman was already having seizures. Ms Howard emphasised that magnesium sulphate injection is now also used as a cheap and effective foetal neuro-protectant to prevent cerebral palsy in pre-term babies, linked to the PReCePT (prevention of cerebral palsy in pre-term labour) initiative. This was one more reason why the maternity network supported the introduction of a safer (more dilute) formulation, she added.

Wider organisational issues contributed to the overall problem – the pharmacy team did not fully understand how magnesium sulphate injection 50% w/v was used and nurses were unaware that other presentations were available. Against this background, a campaign was mounted including a programme of safety seminars for staff, posters for wards and ongoing reporting of usage. In conclusion, Ms Howard stressed that the groundwork does not need to be done again – the Wessex scheme could be adopted elsewhere. However, a licensed product (magnesium sulphate 20% w/v injection) is required, she added.

Failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA) was used in Northern Ireland to understand the risks with magnesium sulphate injection and focus measures to reduce or eliminate them, said Ms Lappin. Calculation errors were identified as being likely to cause serious harm; they arose from misunderstandings about ampoule contents, confusion between units (mmol, grams, % w/v) and lack of awareness of the ‘more than 3’ rule. More than three ampoules are very rarely needed to prepare an injection so if a calculation calls for more than three, the calculation should be checked and help sought. Ready-to-administer (RTA) syringes of magnesium sulphate (5g in 50ml) were obtained, protocols were agreed and a programme was launched in maternity units region-wide. Ms Lappin noted that the implementation of RTA magnesium sulphate injection reduced the risk of errors, reduced delays in treatment and liberated nursing time.

Surviving sepsis

Sepsis accounts for 44,000 deaths annually in the UK – one death every five minutes, according to Georgina McNamara (Executive Lead Nurse for Education, The Sepsis Trust). International recommendations call for treatment with antibiotics and fluids to be started within one hour of sepsis being suspected. However, an audit in 2011–12 showed that only 27% of patients received antibiotics during the first hour. “Every hour’s delay in starting treatment increases mortality by 8%”, said Ms McNamara.

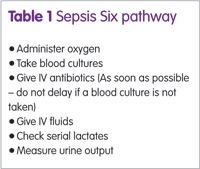

Case examples show that on many occasions, nurses and doctors simply did not know what to do or did not suspect sepsis and patients died as a result. Sepsis survivors can be severely disabled – limbs may have to be amputated – and require long periods of recovery and rehabilitation, noted Ms McNamara. Application of the ‘Sepsis Six’ pathway (see box) can halve mortality.

People should be encouraged to ask, ‘Could this be sepsis?’ if a patient is feverish, shivering or obviously unwell. “Relatives, parents and carers will know if something is seriously wrong with a patient”, said Ms McNamara. Potentially, 14,000 lives could be saved each year in the UK.

Asked if junior doctors might be nervous about giving antibiotics because of pressure to reduce antibiotic prescribing, Ms McNamara said that the issue here is the diagnosis of sepsis. If uncertain, the question should be referred to senior clinician for a rapid decision.

IV flushing best practice

Flushing of cannulae is common practice today but flushing of IV lines after administration is patchy and poorly understood, according to Rachel Dixon (Medication and clinical support specialist, Braun UK). Flushing of IV lines delivers the correct dose, potentially shortens recovery time, prevents wasted clinician time and avoids wasted medicines, she argued.

Failure to flush a line can lead to underdosing. If a dose is prepared in a 50ml infusion bag, it could take 24ml to prime the line, leaving 26ml in the bag. After 26ml has been administered the bag is empty and, in many cases, the line, which still contains 24ml of drug solution, is taken down and discarded, resulting in the loss of about half the dose. This could be a problem, if, for example, paracetamol is being given for febrile convulsions; underdosing could prolong seizures. Surveys show this happens with all drugs – and clinical decisions are made on the basis of underdosed patients, said Ms Dixon. The solution is to replace the bag with normal saline and run until the full volume to be infused has gone through. Some hospitals do this by having normal saline on the discretionary list for nurses. Some staff very resistant to the idea advancing arguments such as, “it costs too much….” It is only a small amount so it does not matter…” “we’ve always done it this way….”, she added.

CSTDs in practice

Closed system transfer devices (CSTDs) ensure airtight and leakproof transfers during preparation of hazardous drugs (HDs) such as those which are teratogenic, genotoxic or carcinogenic and those that cause serious organ damage in low doses, according to Johan Vandenbroucke, (Head of Pharmacy Production, University Hospital of Ghent, Belgium and past president of ISOPP). CSTDs are important because occupational exposure of health care professionals to HDs is associated with serious risks including increased rates of cancer, reproductive problems and damage to internal organs.

Numerous studies in Europe and the rest of the world show the extent of environmental contamination with cytotoxic drugs. There is always some leakage (via droplets or aerosols) if a needle pierces a rubber stopper; only a double-membrane transfer device prevents this, said Mr Vandenbroucke.

In addition, some vials and ampoules are contaminated on the outside when supplied by the manufacturer. High levels of contamination are found in biological safety cabinets and around handling and administration areas. Moreover, cleaning staff may also be exposed to HDs because patients excrete cytotoxic drugs in urine, faeces and sweat.

Staff exposed to cytotoxic drugs have detectable levels of the drugs in their urine and one study showed that staff exposed to cytotoxic drugs developed the signature chromosome changes of myelodysplastic disease. Experts have proposed safe exposure limits for cytotoxic drugs.

Rigorous cleaning procedures help but do not entirely eliminate environmental contamination. Containment is critical to protect staff by preventing the release of HDs in the first place. Studies show that introduction of CSTDs in preparation reduce level of environmental contamination. It is noteworthy that the new US Pharmacopeia standard 800 (USP 800) states that CSTDs should be used during compounding of HDs but must be used when administering HDs to patients (to protect nurses).

Testing CSTDs

Robust testing of the containment performance of CSTDs is essential and a universal performance test protocol has now been developed, Alan Wilkinson (CEO, Biopharma Testing Laboratory, UK) told the audience. A key step in this process was the identification of a suitable drug-surrogate to use as a challenge agent. Initially isopropyl alcohol was suggested but this has a lower molecular weight than most cytotoxic drugs and a much higher vapour pressure. In practice, 2-phenoxyethanol (2-POE) turned out to be much more suitable and this has enabled the development of a test protocol suitable for barrier and air-cleaning CSTDs, explained Dr Wilkinson.

Scanning for safety

The implementation of GS1 codes and PEPPOL (pan-European public procurement online) will make what we do safer, easier, quicker and cheaper, explained Philip Dean (Chief Pharmacist, North Tees and Hartlepool NHS Foundation Trust). GS1 is a global coding system that assigns a unique, machine-readable code to every product, person and place. The PEPPOL protocol will streamline processes in the supply chain, allowing machine-to-machine transfer of purchase orders and invoices. The schemes are not unique to the health service The National Health Service (NHS) is committed to the implementation of both within the next few years. The Carter report predicted that a typical hospital could save £3 million annually through adoption of GS1 standards; overall NHS savings could amount to £1billion over the next seven years. Accurate identification of products and people could prevent medical errors and allow faulty products to be traced rapidly. Mr Dean noted that when the horsemeat scandal occurred, suppliers were able to identify within hours which supermarkets had the products containing horsemeat because of the use of GS1 coding. In future, GS1 coding could allow rapid tracing of patients who had received faulty implants, for example.

At present there are six demonstration sites for GS1 in the NHS, each of which is working through a four-phase, 21-month implementation programme. So far, North Tees and Hartlepool NHS Foundation Trust has completed phases 1–3. This has involved mapping all systems, processes and activities and ensuring that the pharmacy software has GS1 placeholders (that is, is ready to use GS1 codes to identify products). In addition, a PEPPOL-compliant electronic data interchange (eDI) system has been installed and barcode scanners have been trialled. By August 2017, only 44% of products had global trade item numbers (GTINs) and only 20% of suppliers were able to support eDI, commented Mr Dean. Part of the problem was that many hospital systems were designed before GS1 codes were envisaged. Clearly, products have to be scanned automatically when they are received, he added.

Pharmacy technicians administer medicines

One of the medicines optimisation initiatives at Manchester University Hospitals has been the appointment of pharmacy technicians, working a 7.00–14.00 shift, to administer oral doses of medicines on wards, according to Richard Hey (Director of Pharmacy, Manchester University Hospitals). Nursing staff like the scheme and would like it to be expanded because it releases nurses for other patient care activities.

It also reduces the frequency of omitted doses. Training and recruitment for this role has been carefully designed, “it does not suit everyone so careful selection is important”, noted Mr Hey. At Manchester Royal Infirmary the pharmacy technicians who do this are members of ward staff but are professionally responsible to pharmacy, he added.

Changing Practice to Improve Safety was held in Birmingham, UK on 17 October 2017 (Aesculap Academia – supported by B Braun Ltd).